Chapter 12 Betting on Beer (or Ice Cream)

This section makes reference to Chapter 5 of Naked Statistics by Charles Wheelan.

In 1981, Schlitz brewing company, now defunct but at one time the largest beer producer in the US, ran a bold advertising campaign. During the Super Bowl, Schlitz ran a live blind taste test against one of its competitors, Michelob. 100 Michelob drinkers participated in the taste test, which aired LIVE. The advertisement slot itself cost a lot of money. Schlitz could have just run a funny ad involving puppies on the beach, so why take a risk with a taste test that could conceivably have gone badly. How could Schlitz have been so confident that their beer would be preferred?

THINK ABOUT IT QUESTION: What information would you need to know to advise the Schlitz brewing company about running such an ad? (Take a few minutes before continuing on, to try to list this information on your own).

As discussed in Wheelan’s chapter, some things we would need to know are:

- Actual proportion of Michelob drinkers who would prefer Schlitz in a blind taste test

- Acceptable outcome of live taste test for promoting Schlitz beer

- Intended sample size for taste test

- Rules of mathematical probability

Wheelan adds a lot of context to this particular story, which is part of the fun. In particular, he asserts that Schlitz and Michelob are probably indistinguishable to most beer drinkers. This puts the chances of anyone prefering one beer over the other at 50%. He also points out that the marketing campaign works well for a range of outcomes, because the taste test is conducted with Michelob drinkers. Schlitz executives will be quite happy to be able to say that even 40% of Michelob drinkers prefer Schlitz, which sounds (and is) very different from saying that 40% of all beer drinkers prefer Schlitz over Michelob.

Wheelan invokes the “law of large numbers” to argue that for a given sample size, and if the actual proportion is 50%, that the results of the live taste test can be almost guaranteed to be satisfactory for Schlitz (we define satisfactory, for now, as at least 40% preferred). The larger the sample size, the greater the probability that the taste test will be a success. We have created a Schlitz simulation for you to explore this for yourself.

In his book, Wheelan claims that (a) for 10 blind tast testers, the probability of a happy outcome is 0.83 and (b) for 100 blind taste testers, the probability is 0.98. If you don’t want to take this assertion at face value, you might try convincing yourself by opening the simulation, running 100 simulated experiments of sample size 10 or 100, and inspecting the proportion of those experiments that led to a favorable outcome. You should see values around .83 and .98 for sample sizes of 10 and 100, respectively.

For a moment, let’s pull back the curtain on the Schlitz simulation and see how it works. The following code walks through the process of repeatedly surveying 10 people, recording the proportion who preferred Schlitz (under the assumption that each person has a 50% chance of preferring Schlitz), and calculating the proportion of those 10-person surveys that led to an acceptable outcome. If we collect 10,000 samples of 10 people and calculate the proportion of those 10 person samples where at least 4 out of 10 people preferred Schlitz, we can estimate the probability of an acceptable outcome very accurately:

numExpts = 10000 #set some number of repeated experiments to run

sampleSize = 10 #set the sample size

trueProb = .5 #set the (true) probability of preferring Schlitz

acceptableOutcome = .4 #set an acceptable proportion of Schlitz preferrers

results = vector(length = numExpts) #create a vector of length nIter

for(i in 1:numExpts){ #repeat the following process numExpts times

#Choose sampleSize-many values from the set (0,1) with replacement

#where the probability of drawing a 1 is equal to trueProb

#save the results in a vector called drawResults

drawResults = sample(c(0,1), size=sampleSize, prob=c(1-trueProb, trueProb), replace=TRUE)

#In the ith location of "results", calculate the proportion of 1s in Samp

results[i] = sum(drawResults)/sampleSize

# NB: this would also have worked

}

#Calculate the proportion of random experiments that were "acceptable"

sum(results >= acceptableOutcome)/numExpts## [1] 0.834Feel free to copy this code over into your own script in RStudio and play with the parameters to see what happens. If you decrease numExpts to 1000 and re-run the simulation a few times, you might see that there is more variation in the estimated probability; however, if you increase numExpts to 100000, you are more likely to observe values very close to .83 every time. That is, the sampling variance is larger for small samples and smaller for large samples.

How do statisticians solve problems like this?

In this course, I have tried to emphasize conceptual understanding through simulation and discussion. In the example above, you can, for example, run a bunch of simulations of the experiment and (very accurately) estimate the probability of an acceptable outcome. But, you’ll get slightly different answers each time you run the simulation. If this bothers you, read on.

Mathematical statistics does have precise answers that depend on properties of continuous distributions like the normal distribution and the binomial distribution. The term data distribution comes from trying to describe how data or observations are distributed across the values that they can attain. For example, are all outcomes equally likely? (A uniform distribution.) Or are values near the “middle” more likely than values farther away? A histogram is one way to visualize a distribution, and we often speak of the “shape of a distribution.” The normal and binomial distributions (which are both bell-shaped, by the way) are idealizations that are realized if we have an infinite amount of data. In reality we only have finite samples. But when we have large enough samples, even though they are not infinite, their data distributions start to look more and more like their idealized versions.

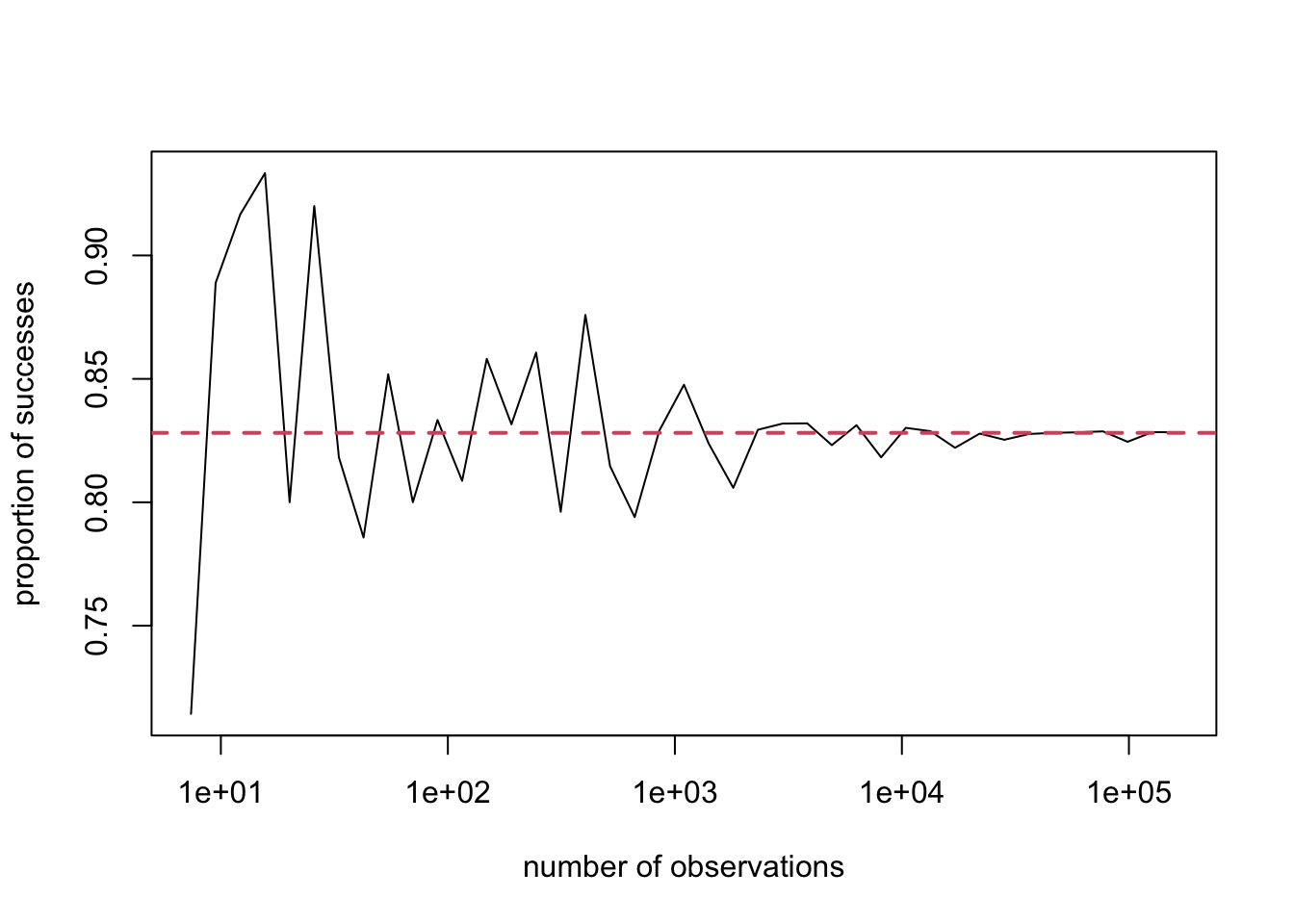

The Schlitz commercial is exactly the kind of scenario that is explained using a binomial distribution (more on that later). If we ran the simulation (always with samples of 10), taking more and more observations (i.e., 100 samples of 10, 1000 samples of 10, etc.) and checked our success rate (defined by at least 4/10 preferring Schlitz), we would see that indeed this proportion does converge. This is plotted in Figure 12.1. The x-axis is the number of samples, but note that the x-axis is shown using logarithmic scales. We need to use this scale, or else all of the points at smaller values would be bunched together. (Try this at home: draw an x-axis and label one end 0 and the other end 100,000. Now try placing tick marks at the values 10, 100, 1000, and 10,000.)

Figure 12.1: Convergence of successful tasting proportions

So we see that there is some convergence: If we run more and more experiments, we find that the proportion of “successful” experiments converges to a stable value. But how can you calculate that value precisely? To find the analytical (i.e., exact) answer, instead of using a simulation to estimate it (empirically), it helps to start with a small sample size, say 2. Now that we’ve reduced our scope, we have some hope of writing all possible outcomes of this experiment and their probabilities.

What are all of the possible outcomes of 2 independent taste tests? We are using the word independent here, because we believe that one person’s preference in a blind taste test does not influence the preference expressed by another person. If the same person were asked to do the taste test on two occasions, it might not be appropriate to treat those two results as independent. Unless the beers are truly indistinguishable. In any case, we are assuming that we have two strangers.

Aside: To be more precise, we should say that the two strangers’ answers are conditionally independent, because their preference does, in principle, reflect the quality of the beer. Suppose I told you that I had two beers, a horrible one and a delicious one. And that I was going to put them to a blind taste test. I don’t tell you which is labeled beer A and whcih is beer B. I tell you that one person preferred beer A. Now another person comes to take the test. Which do you think they will pick? Probably beer A, because that one is probably the delicious one. So it looks like knowing what one person chose provides information about what the other one will choose. Which seems to violate the definition of independence. We can condition this association away. The answers are not causally associated, but rather indirectly associated by the fact that they are both explained by the “true” taste of the beer. That is our third, or lurking, variable here. I didn’t tell you whether beer A or B was the delicious one. You tried guess which it is, based on the one observation of preference for beer A. However, if I told you that in fact beer B is the delicious one, but one out of twenty people seem to prefer beer A anyway, then this would change things. Knowing that one person came along and picked A would not make you predict that the next person will do the same. You will still, if you take my word for it, predict that the next person (and almost all of the people to come) will choose beer B. The formal way to put all of this together is that conditioning on the known desirability of the beer, each individual taste test is independent of the others. In the example above, we assumed that the chances are 50/50, but they didn’t have to be for the conditional independence of trials to hold.

There are two possibilities for each taster (either Schlitz or Michelob), so if we represent each possible outcome as (taster 1’s choice, taster 2’s choice), we get 4 possibilities.

{(Michelob, Michelob), (Michelob, Schlitz), (Schlitz, Michelob), (Schlitz, Schlitz)}The possible outcomes of a random experiment form a set, which is called the sample space. As per convention, we use curly brackets to indicate the set. The elements of the set are the outcomes, and we use ordinary parentheses to indicate the ordered pair of (Taster1, Taster2). At this point, you might find it helpful to look back at Chapter 10 to refresh your memory.

Because each individual taste test is independent, we already know how to express the (joint) probability of an outcome involving multiple tasters in terms of the individual probabilities. For example, the probability of (Michelob, Schlitz) is:

P(Michelob, Schlitz) = P(taster 1 prefers Michelob AND taster 2 prefers Schlitz)

= P(taster 1 prefers Michelob) * P(taster 2 prefers Schlitz)

If we assume that every taste tester is equally likely to prefer either beer, then

P(taster 1 prefers Michelob) = 0.5 = P(taster 2 prefers Schlitz)and so P(Michelob, Schlitz) = (.5)*(.5)=.25. In other words, there is a 25% chance that the outcome of the experiment is that the first taster prefers Michelob and the second taster prefers Schlitz. In fact, assuming a 50% chance of preferring either beer, we’ll get the same probability for any of the four outcomes.

Notice that the four outcomes listed above are disjoint (only one can occur) and complete (one of them MUST occur). Therefore, we also knew that their probabilities must add up to 1. And since they are also equiprobable, we could have known that each probability must by 0.25.

Now we can ask: which of the four possible outcomes will meet our requirement that at least 40% of respondents prefer Schlitz? Probability textbooks often use the word event to describe some subset of the sample space for a random experiment. An event can be one outcome, a subset of one, but it can also span several outcomes. In this case, we could describe the event that at least 40% of respondents prefer Schlitz as the set: Acceptable = {(Michelob, Schlitz), (Schlitz, Michelob), (Schlitz, Schlitz)}. If the probability of each outcome is 0.25, then because the outcomes are disjoint, the probability of “Acceptable” is

P(Acceptable) = P(Michelob, Schlitz) + P(Schlitz, Michelob) + P(Schlitz, Schlitz)

=0.25 + 0.25 + 0.25 = 0.75Notice that because all of the outcomes are equally probably, the probability of an acceptable outcome reduces to the number of acceptable outcomes divided by the total number of possible outcomes. In this case, 3 out of 4, or 75%.

Excercise: How would the probability of an acceptable outcome change if we believed that each taster had only a 40% chance of preferring Schlitz (and a 60% chance of preferring Michelob)?

After all this work, you might be thinking: well that’s all fine and good, but it’s a lot of work to write out the sample space and list of acceptable outcomes for a sample size of 10 or even 100. You’d be right. For larger sample sizes, we need to employ some new techniques and R functions (which are only briefly covered in this text). But, for the sake of completeness, let’s briefly examine two ways to conceptualize the problem and calculate the analytical probabilities in R. Don’t worry if it doesn’t make perfect sense yet; we won’t make you do this by hand!

The solution by counting, or combinatorics

First consider the simple case above, where tasters are equally likely to prefer Schlitz or Michelob. Because all individual probabilities are equal, all joint probabilities are equal—e.g., the probability of (Michelob, Michelob, Schlitz, Michelob) is the same as that of (Schlitz, Michelob, Schlitz, Michelob). We can calculate the probability of an acceptable outcome (at least 40% preferring Schlitz) among 10 tasters by figuring out (i.e., counting) how many of the possible outcomes are acceptable outcomes. The total number of possible outcomes is \(2^{10}\) for a 10 person sample size (this is the same math as in the calculation of how many types of people you could observe by asking \(10\) independent, dichotomous questions).

One acceptable outcome would be if everyone chose Schlitz. But it would still be acceptable if 9/10 of the tasters chose Schlitz, and there are 10 different ways that could happen, because the Michelob chooser could be in position 1…10 in the order. We are going to have to follow this logic down to 8, 7, 6, 5, and 4 out of 10 (since all would be acceptable). So we nned to dust off the old choose() function. If you’ve never seen it before: choose(n,k) (read “n choose k” and often written \(n\choose{k}\)) is the number of possible ways to choose k items out of a group of n total items. In this context, choose(n=10,k=4) is the number of unique groups of 4 tasters among a total pool of 10 tasters (i.e., number of ways that exactly 4/10 tasters could prefer Schlitz). In R:

#calculate choose(n=10,k=4) in R

choose(n=10, k=4)## [1] 210#calculate choose(n=10,k= all the numbers between 4 and 10)

choose(n=10, k=4:10)## [1] 210 252 210 120 45 10 1#add up all of the values above using sum() and then divide by 2^10

sum(choose(n=10, k=4:10))/2^10## [1] 0.828125Excercise: Can you modify the above code to calculate the empirical probability of an acceptable outcome for a sample size of 100 (again assuming preference for Schlitz and Michelob are equally likely)?

The solution by distribution, or statistics

The above combinatoric method won’t work if the outcomes are not equally probable. We may want to account for different probabilities of preferring Schlitz or Michelob. Maybe it’s 43% to 57% and not 50/50.

Now we will need to call upon the powers of the binomial probability distribution. This function and its relatives can answer questions such as what is the probability of 42 successes in 89 independent trials, each of which has a 0.44 chance of being successful. Of course those numbers are arbitrary. In R, the function dbinom(x,n,p) gives the probability of x “successes” in n independent random trials, where each random trial has probability of success = p. For example, dbinom(4,10,0.5) is the probability that exactly 4 out of 10 people prefer Schlitz if the probability of any individual preferring Schlitz is 0.5. Using this function, we can now repeat the calculation above using some slightly different code:

# calculate a few individual values, e.g., dbinom(4,10,.5)

dbinom(4,10,0.5)## [1] 0.2050781dbinom(5,10,0.5)## [1] 0.2460938dbinom(6,10,0.5)## [1] 0.2050781#add up the probabilities of 4,5,6,7,8,9, or 10 people preferring Schlitz

sum(dbinom(4:10,10,0.5))## [1] 0.828125Exercise 1: Can you explain why choose(n=10, k=4)/2^k is equal to dbinom(4,10,.5)?

Exercise 2: Can you modify the code above to calculate the probability of an acceptable outcome if each taster only has a 40% chance of preferring Schlitz?

If these calculations feel a little overwhelming and confusing at this point, don’t fear! Instead, revel in the fact that you just got (approximately) the same number using three different conceptualizations of the same problem. The point is: there are many ways to answer probabilistic questions, and simulation can be a powerful tool to side-step advanced probability calculations.