Chapter 8 When and How Will You Die?

It is difficult to make predictions, especially about the future.

— Niels Bohr (probably)

In our first Big Question, we began to look at individual differences between people or what statisticians call variation within a population. If there is no variation—like in the bizarro world where everyone orients their toilet paper in the “under” orientation—then there is nothing to talk about, at least not statistically speaking. There is, however, considerable variation in health outcomes and human lifespan. Lots to talk about there. In our next Big Question, we ask “when and how will you die?” and “what, if anything, can you do about it?”

What kind of question is, “when and how will you die?” Well, according to some of my colleagues, it is a morbid question. Feelings aside, we might say that it sounds like a prediction question, since it is about the future. So to explore this big question, we will need to understand what it means in general to make a forecast about some future event. We’ll also find it useful to distinguish between predictions that are or are not explanatory. Most efforts in health sciences attempt to explain relationships between behavioral and genetic factors and health outcomes. In particular, they try to understand causal effects. So in the next few chapters, we will also try to understand causal explanations more generally.

Not Quite Death, but, um… Rain?

Perhaps it is a good idea to warm up, before we face the grim reaper. What does it mean to say there’s a 30% chance of rain tomorrow in New York? Does it mean that it will definitely rain in 30% of the city (say, Brooklyn), but not in the other 70%? Or that it will rain for 30% of the day (say, from 8am-3pm). Here are some possibilities to consider:

- It will definitely rain in some parts of the city but not in all of them

- It will definitely rain for some part of the day in all of the city

- It will definitely rain for some part of the day in some of the city

- It may or may not rain anywhere in the city at any point in the day.

Read here for an explanation of what meteorologists probably mean

Stochastic vs Deterministic relationships

Sometimes when I say definitely, I mean probably. Like if I say, I’m definitely going to do something about all of this clutter on my desk. But when I really mean business, I say deterministically. It definitely sounds more serious.

Meteorologists—scientists who model the weather—cannot tell us deterministically about weather events. Recall that we previously considered deterministic associations between two two-kinds-people questions. We imagined a world where if you knew a person’s answer to one question (e.g., are you right- or left-handed?) then you would know for sure their answer to another. Now some of our examples were hypothetical and unrealistic, because, well, people are not in actuality very deterministic. If we want realistic examples, we end up making use of tautologies like “Are you single? Are you in a relationship?”

But some events in nature are, more or less, deterministically related. An example might be something like, if I let go of the umbrella I am holding, then it will fall to the ground. If A then B. No exceptions (and no strings). You can imagine that I asked two questions: (a) did I let go of the umbrella (at a certain time T)? and (b) immediately after time T, did the umbrella fall to the ground? If you know the answer to one question, then you know the answer to the other.

Weather events are stochastic. As we know all too well from experience, they have an element of chance or randomness, like tossing a coin or rolling a die. So, just as we can say that a coin has a 50% chance of coming up heads—assuming it is a fair coin—we can make statements like there is a 30% chance that it will rain tomorrow. Stochastic is another word for random, but I prefer it because the word “random” is often used casually to mean weird or unusual (as in, “that’s random!”) Although we can’t speak with certainty about random, or stochastic, events, that doesn’t mean we can’t speak usefully about them. We just need to learn to speak probabilistically.

Ways of thinking about probabilistic statements

Ensembles

One way to think about the 30% chance of rain is to imagine that our experience in the world is one possibility in a multiplicity of possible worlds. See, I told you this idea of multiple alternate universes was going to be important! Imagine that there are 10 possible worlds, indistinguishable from ours in terms of the laws of physics, and that tomorrow it will in fact rain in 3 of them. To the great being-who-knows-all-things, which 3 worlds will see rain may well be known. However, to us mortals who merely live in the world that we know, we don’t know which one of these possible worlds is the one we live in. Nevertheless we are capable of imagining these different potential outcomes. As you just did.

It didn’t have to be 10 worlds, of course. That was arbitrary. If we imagined thirty worlds, it could rain in 9 of them, as I’ve represented in Figure 8.1. I did this by making thirty circles and coloring in 9 of them at random. Since I like to pull back the curtain every once in a while, I will even show you the R code I use to generate this simple figure.

# start with a 10 x 3 grid of points

norain <- cbind(rep(1:10,3), rep(1:3, each=10))

# choose (sample) nine at random, using the sample() function in R

rainworlds <- norain[sample(1:nrow(norain), 9),]

# plot the points

plot(norain, xlab="", ylab="", ylim = c(1,3), axes = FALSE, asp = 1)

# color in the nine

points(rainworlds, pch=19, col="lightblue")

Figure 8.1: Rain (filled, blue dots) in 9 out of 30 possible worlds. It does not rain (hollow circles) in the other worlds.

Using this ensemble of possible worlds provides us with a sense-making device for probabilistic statements. Ultimately, it either will or will not rain tomorrow. You can also think of this observation as sampling from the ensemble of possible worlds. As though we put them all of these worlds into a hat and drew one of them. The probability of an event is thus thought of as the frequency with which it occurs.

Degree of belief

There is another way to think about 30% as a probability. Suppose a meteorologist said to you, I’m 30% sure it is going to rain tomorrow. And you say back, “Oh, you mean that, say there are really 1000 alternate universes out there, that in roughly 300 of them, it will rain tomorrow?” And the meteorologist says, “I have no idea what you’re talking about. There is only one universe, and I’m not totally sure what will happen tomorrow, but I put the chances of rain at 30% [walks away slowly towards the door].”

For your meteorologist friend, let’s call them Mel, 30% may represent a degree of belief. Importantly, the degree of belief is subjective. Here it is attributed to a meteorologist, which might make you take it more seriously than if your Uncle Bob said the same thing (unless Uncle Bob is actually a meteorologist). Anyway, degree of belief is subjective. Which doesn’t mean it is arbitrary or just a matter of opinion. When it comes to forecasts, some people or some forecasting models are going to be right more often than others.

This idea of “being right more often” helps us connect the degree of belief way of thinking about probability to the ensemble sampling idea of probability. Sure, tomorrow only one universe will be ours to observe. It will either rain or not. If it rains, will you say that Mel the meteorologist did a good job or a bad job? What if it doesn’t rain? It’s going to be hard to say based on a single observation!

But a few days or weeks from now, Mel (the meteorologist) will come along again and say there is a 30% chance of rain tomorrow. And again. And again some time later. What we could do is collect all of the times that Mel gave 30% as their chance of rain and compare the actual occurrence of rain the next day. Suppose that we have 88 such cases to examine, and that it rained in 30 of them. Thats 30/88 or 34% of the time. While not exactly 30%, that still seems pretty good for something as complex as the weather!

Now maybe, maaaaybe, we could wonder if Mel is in fact under-predicting the chance of rain. Then we could add a bit to their forecasts when deciding what to do about it. I would feel more confident about that if we had a larger sample size. This is because we know that the observed proportions in a stochastic process will only converge to “true” proportions when sample sizes get large. We will come back to this in the module about money.

To recap, out of 88 times that Mel gave a 30% chance of rain tomorrow, it rained the next day 30 times and didn’t rain the next day 58 times. You can see why it’s hard to judge the meteorologist based on a single observation, even though we are often personally annoyed when the event (rain/no-rain) does not coincide with the choice we made about whether to wear galoshes.

Decisions

Aside from subjectivity, which is a thorny topic among statisticians, there is really no practical difference between the interpretation of 30% probability as a frequency of occurrence in an ensemble of possible worlds or as a degree of belief about this world. It won’t change what you do about it.

If you take this forecast of rain seriously, you have decisions to make. It could be whether or not to take an umbrella with you when you leave the house tomorrow, or whether to cancel your plans to have a barbecue outside. These decisions may not seem very high stakes. The worst case scenario is that you (and others at your barbecue) get wet. But other decisions you have to make on a daily basis can have more serious consequences for your health or even your life. You often have to make those decisions based on probabilistic and maybe subjective information.

Death

End of warm-up. It’s time to talk about when you will die.

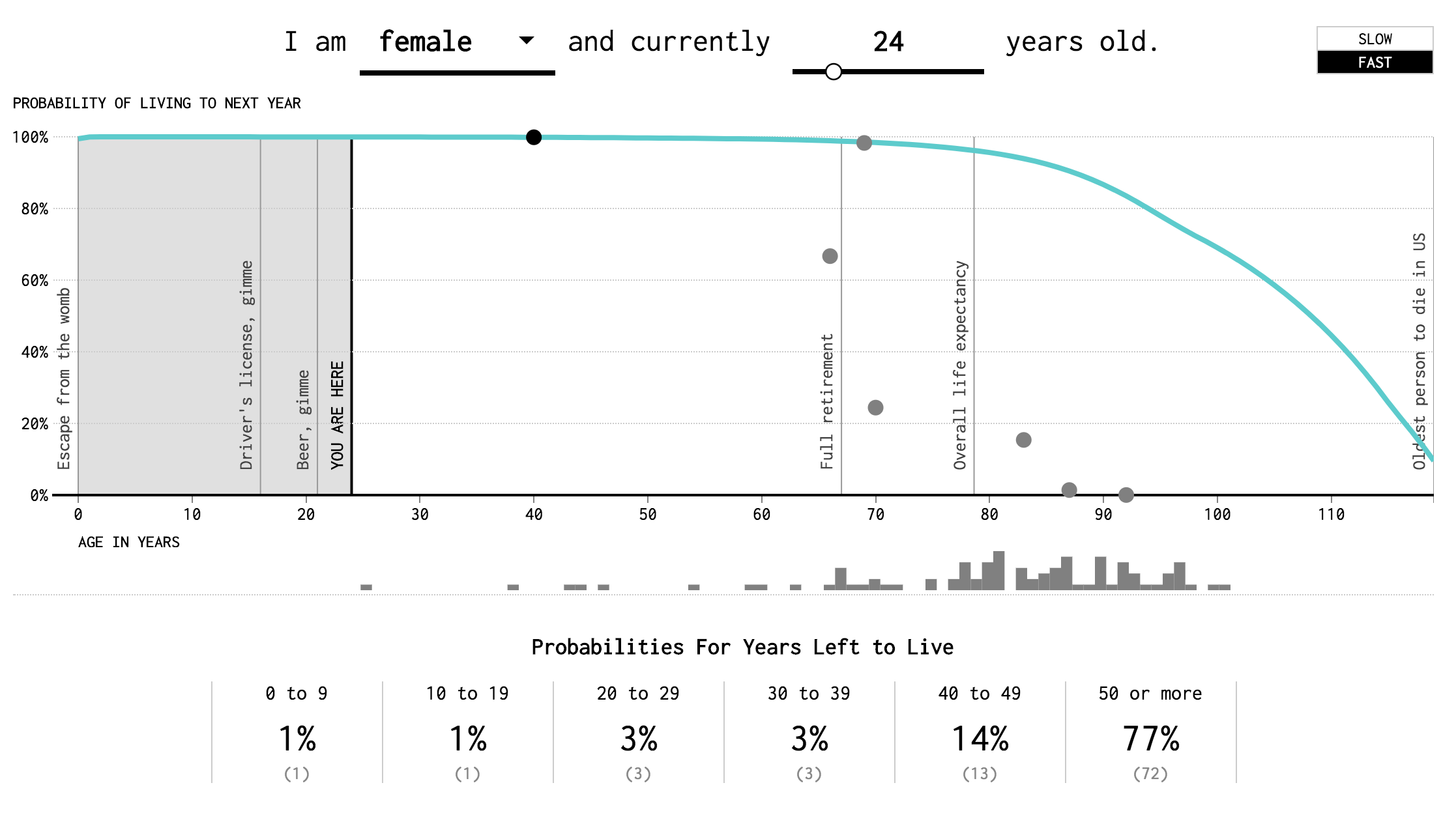

I highly recommend this data visualization called Years You Have Left to Live, Probably. Here is a screenshot, although it’s not nearly as interesting when you can’t interact with the simulation and watch the little balls drop.

Figure 8.2: Screenshot of interactive data visualization

This visualization does a number of things. The most salient feature is probably the dropping balls. Each one represents a possible future outcome. This is exactly like an ensemble of alternate universes. As you watch the balls drop, you think to yourself, “ah, nice, I lived to be 92” and then moments later, “ooh, harsh! I died at 39!”

As the simulation runs, it also accumulates data in bins at the bottom, labeled “0 to 9”, “10 to 19”, and so on. (Recall the discussion of bins, frequency tables, and histograms in Chapter 4.) Note that these bins represent ranges of years-you-have-left-to-live, not age-at-death. This may be confusing, because age-at-death is what is shown along the horizonatal, or x-axis, of the figure. Also, right below the x-axis, and corresponding to age-at-death is a set of gray bars that grow as the balls drop. In the screenshot, the simulation has been running for a little while, so that the following counts have been accumulated.

| bin | counts |

|---|---|

| 0 to 9 | 1 |

| 10 to 19 | 1 |

| 20 to 29 | 3 |

| 30 to 39 | 3 |

| 40 to 49 | 13 |

| 50 or more | 72 |

Notice that by the time this screenshot was taken, 93 balls had dropped. The visualization took the counts, converted them into proportions of total counts (e.g., 72/93 = 0.774; 3/93 = 0.33), and represented each of these proportions as a probability, expressed as a percent (e.g., 77%; 3%).

Another thing that you will notice if you play around a bit is that as the balls drop, the probabilities change. In the beginning, when the number of samples (balls dropped) is small, the numbers change rapidly and sometimes by a large amount. However, after a couple of hundred samples, the changes are much smaller.

By watching the balls drop on this simulation (which I, for one, find mesmerizing), you may actually be meditating on some profound ideas in statistics. Every time you restart the simulation, you begin the sampling process. Each sample is a draw from some distribution of possible life outcomes. Your future life bounces around in this distribution from sample to sample. And in the beginning, when you have only collected a small number of samples, the distribution itself seems unstable. For example, if you put in 24 as the current age and start the simulation in slow mode, the estimated probability of living 40-49 more years fluctuates a lot. However, as you accumulate samples, the shape of the distribution literally comes into view as a pattern among the gray bars just below the x-axis. As the sample size increases, the probabilities becomes more stable. Eventually, if you let it run long enough, you end up with the same values, regardless of how things started out. (This increasing stability at large samples is why I was hesitant to judge Mel the meteorologist until I had more data.)

Although we are now talking about probabilities about your remaining years left to live, the interpretation of probabilities is similar to that in our discussion of rain predictions. In the case of rain, there were only two possibilities, rain or no-rain. (A dichotomy!) In the death simulation, there are six bins, each of which represents a range of years. In the case of rain, we understood the meaning of a 30% chance (i.e., probability) of rain by imagining a large number of possible worlds, where it rains in 30% of them. Or one universe where there are a lot of opportunities to make forecasts and check the restults of them. Thus the probability was associated directly with a frequency of something occurring. This is known is as the frequentist interpretation of probability. In the case of death, we say you have a 77% chance of living 50+ more years if, in a large number of possible worlds, you live 50+ more years in 77% of them.

You probably realize that we don’t get to see all of these alternate universes, even though we can imagine them. Therefore our probability estimates in many cases are based on things that we have observed happen to other people. For example, among 100,000 people that we do observe from the moment of birth, suppose 78% of them lived into or past their 70s. We convert that observed frequency into a probability for you. You could say that we treat the other people we observed as alternate-universe versions of you.