Chapter 13 Expected Value

Betting on ice cream

The Schlitz example feels a bit contrived, at least to me, because in the scenario, the Schlitz executives don’t really care about the truth. They just care about what will play well to Super Bowl audiences. Nevertheless, we can see the beer taste test as an example of a sampling procedure. We sample from a population (e.g., 100 beer drinkers) to make inferences about the whole population (100 beer drinkers).

You saw—using the simulation—that whenever you collect data from a sample, you get slightly different results. In this case, you observe a sampling distribution in the observed proportion of Schlitz-preference. It had that bell-shaped curve. I want to show you that the same simulation can be used to help you resolve your bet with your friend about whether most people prefer mint chocolate chip or cookies and cream as flavors of ice cream.

Let’s now return to the ice cream bet that you made with your friend. Now some people just like to bet on any random event like dice rolls and wheel spins; we’ll come back to gambling later. But when you bet your friend, it’s often because you think you are right, but you acknowledge that you are uncertain. Your hunch is that the true value of ice cream preference is greater than 50% in favor of mint chocolate chip. By true value, I mean the answer you would get if you could literally ask everyone in the world this question or, to save time, if you could consult the all-knowing-one and just ask them. This conviction is important, because if both you and your friend believe the proportion really is 50/50, then you are just betting on a coin toss. Which is cool, if you want to do that.

Suppose you believe that the true value is 65%. Just about two out of three people prefer mint chocolate chip. Your friend thinks the edge goes slightly to cookies and cream, but not enough to notice, and what’s the point of betting on a coin toss. You want to make a point, though, so you’re willing to go out on a limb. You say, “Friend, I will give you 3 to 1 odds on this bet. If you lose, you pay me $3, and if you win, I will pay you $9.” It works. Your friend becomes interested.

Now that the stakes have been raised, you and your friend start negotiating terms. You both agree that people in Washington Square, for the purposes of this bet, represent an unbiased sample. You are not, for example, offering to poll people at the I-heart-Mint festival. You have limited time, but you agree to ask 10 people (you can each pick 5, just to make it fair), and everyone polled has to pick one preference (no ties). If at least 6 out of 10 prefer mint chocolate chip over cookies and cream you win; 5 or fewer and your friend wins. These are the terms.

Assuming you’re right about the true proportion, will you make money?

By now you know that you are still not guaranteed to observe proportions of 6.5/10 because (a) you can only observe 6 or 7, not 6.5, in a sample size of 10 (no ties!) and (b) because there is variance in the sampling distribution. You want to know the probability of winning the bet, so you can decide whether you gave your friend good odds or maybe you were too impulsive.

You can use the Schlitz simulation tool even though this is a bet about ice cream. If you use the simulation tool and take 10-person samples one-at-a-time and setting the true probability to 0.65, you might find something like this: 6, 6, 7, … so far so good!… 5, 8, 5, … uh oh, you would have lost 2 out of 6. If you use the Run 100 times feature of the simulation, you might get 70%, 72%, 78%, 75%, 80%, … so it looks like your chances are maybe around 75%. You reason as follows: I have a 75% chance of winning $3 and a 25% chance of losing $9.

Worked example: Calculate the exact probability using dbinom() in R.

We can work out the solution in these steps:

- We assume that the true probability in the population for preferring one flavor is 0.65

- A “successful” outcome, if we ask 10 people, would be confirmation from 6, 7, 8, 9, OR 10 of them.

- Since these are disjoint outcomes, the probability of getting any one of them is the sum of the individual probabilities.

dbinom(x, size, prob)will tell us the probability ofx“positive” results in a sample ofsize, when individual probability isprob, so- We want to sum up this expression with

size = 10,prob = 0.65, andxranging from 6 to 10 sum(dbinom(6:10, 10, prob=0.65))= 0.7515

By the way, the probability of 5 or lower success is known as the complement event, and by definition it must be equal to 1 minus the probability of 6 or higher. Similarly P(6 or higher) = 1 - P(5 or lower), and indeed 1 - sum(dbinom(1:5, 10, prob=0.65)) also works.

Exercise: If we changed planned to ask only 5 people, how would you compute the probability of a winning bet using dbinom() in R?

The weighted average of these two outcomes is called the expected value of the bet. That is, each outcome has a probability and a dollar-valued return, including possible loss. You “weigh” each return by the probability of it occurring. This is done by multiplying each outcome in dollars by the probability of that outcome and adding up the terms. We need to consider losses of money as negative dollar-returns, so

Expected Value = P(outcome 1) * Return(outcome 1) + P(outcome 2) * Return(outcome 2)

= 0.75 * 3 - 0.25 * 9 = 0

(By the way, weighted averages are not always weighted by probabilities. For example, a course grade may be determined as 50% exams, 30% papers, and 20% homework. But weights, and probabilities, must always add up to 100%, or probability = 1, if you include all of the components. If we were more careful, we should probably call them proportional weights. Course grade weights are deterministic, but in expected values that weights are probabilistic.)

What does it mean that your expected value (or expected return) for your ice cream bet is 0? For one, it means that you are just as likely to win money as to lose money. In other words, you have proposed a fair bet. Which is the nice thing to do, since after all this is a friendly bet. Your friend originally thought that the two flavors were equally preferred. Given the odds you offered, what was the expected value from your friend’s point of view? (Answer in the footnote).9.

You might now see the relationship between “odds” language and probability language. In the example, we refered to 3 to 1 (or 3:1) odds for the bet. The probability of winning (assuming you were right about the true preference rate) was 0.75. This is three times as high as the probability of losing, which was 0.25. So you made the bet fair by making the payout proportional to this ratio. In fact, the formal definition of odds in mathematical probability is exactly this ratio of the probability of an event divided by the probability of its complement, or p/(1-p). When the probability is 0.5, this ratio is 1. We say that odds are 1:1 (1 to 1) or use the funny-by-coincidence term “even odds.”

Exercise: What would the expected value from your and your friend’s perspective have been if the odds given were 2 to 1 instead of 3 to 1 on a $3 bet? Hint: 2 to 1 odds means you are willing to lose $6

If the bet described above took place, there would be one outcome. Either you win $3 from your friend or they win $9 from you. The expected value of 0 will never actually occur. But, as we often like to do, we can imagine 100 (or one million) alternative universes to ours. Assuming the probability calculations above, you win the bet in roughly 75% of them and lose the bet in 25% of them. This is what we meant by the probability in the first place. The expected value can be thought of as your average earning across all of these multiple universes.

By the (Statistical) Power of Grayskull

Sidney says: From playing with the simulations, I have noticed that the range of observed proportions is the true value (say, 0.65) “plus or minus” some amount of variation due to sampling. Furthermore, the variation became smaller as the sample size got larger. I had a 75% of observing a majority when the sample size was 10. But by increasing the sample size to 100 or 1000, then the chance was much higher.

This narrowing of the distribution, or the reduction in “error variance” due to increased sample size, is related to a statistical concept called power. This term often comes up in relation to hypothesis testing. When researchers do a study, they want to make sure the sample size is large enough. Even if the alternative hypothesis is correct, small samples may mean that the data are still consistent with null hypothesis. For the example above, the alternative hypothesis test was “more than half prefer mint chocolate chip” and the assumed true value for the proportion was 0.65. With a sample of 10, your power was 0.75. Note that your power came from two sources. One was the size of the difference you wanted to detect, i.e., the effect of mint chocolate chip preference. You believed that this effect was reasonably large at 0.65. A preference of 0.52 would be harder to detect in a sample of 10, while a preference rate of 0.91 should be easier. Thus in the latter case, your sample study would have higher power than in the former case (low power).

You can’t typically control the size of the effect. It is what it is, and perhaps if the effect is small, you may not care as much about it. However, some knowledge is still worth pursuing, even of small effects, and you can often control the size of the sample. Increasing the sample size increases your power to detect effects, even small ones. When scientists design a research study, they will often conduct a power analysis in advance to determine the sample size necessary to make confident claims about the effect of interest. This is analogous to what Schlitz marketing would have had to think through in deciding how many people to include in their live taste test campaign.

Betting on your Future

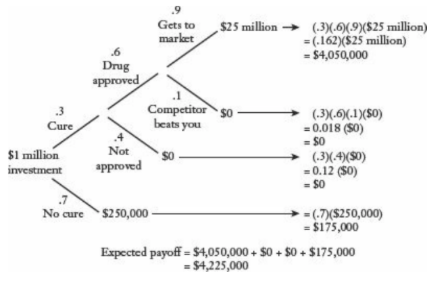

Consider the Investment Decision diagram of Naked Statistics, Chapter 5, that you read at the beginning of this module. The diagram is reproduced in Figure 13.1

Figure 13.1: Drug trial tree diagram (source: Wheelan)

This figure represents the drug approval process from investment to pay off in the form of a tree.10 At each branch-point of the graph, there are two possibilities: first, you may or may not develop a drug that cures a particular disease. Next, even if the drug works, it may or may not get approved. And even if it gets approved, it may or may not make it to the market. At each branch, there are also two probabilities corresponding to each path. The end-points of the branches are the leaf nodes of the tree diagram. In this particular tree, one of each forking paths is always a dead-end, or leaf. But the tree can branch in other ways.

Here are some questions to consider

- The final probabilities at each end-point are products of the probabilities along the path to get there. Why?

- How do you think we estimate these branching probabilities in practice?

Why why why multiply-ay-ay?

For the first question, you might reason through the probability “math” as follows. Say this drug investment happens in 1000 alternate universes. In 700 of them, the drug turns out to be a dud, and there is nothing more to say. But in 300 of them it is a wonder-cure. Of the 300 universes in which the drug worked, it is not approved for use in 120 but is approved for use in 180. And so on. This winnowing-down or funneling of our imagined 1000 cases shows that you must keep applying these proportional cuts in sequence. That is, you take 0.3 of the starting amount (300/1000), and then 0.4 of that mount (120/300), which is equivalent to multiplying 1000 by 0.3 and then 0.4. Note that the language in the italicized phrase (“of the…”) is suggestive of the language of conditional probabilities (e.g., “given that…”). This hints at another, perhaps more formal, description of why we multiply probabilities along the path in the tree.

To get to the endpoint, for example that “a competitor beats you to market,”, three things need to happen. The drug must be a cure, it must be approved, and the competitor must beat you. These are three events, and the probability we need in order to compute expected value is the joint probability of all of them. That is, P(Cure AND Approved AND Beaten) or P(C, A, B). It is tempting to invoke the rule for independent probabilities to explain why this joint probability is the product of the individual probabilities. But it would be missing an important subtlety. These events are not independent; they are only conditionally independent. The probability of being approved is zero if the drug is not a cure. So we clearly cannot say that knowing the drug is a cure does not change our expectation of its likelihood of approval.

Rather, what is happening here is that we are multiplying conditional probabilities. And we are doing so in accordance with the definition of conditional probabilities that we saw in Chapter 10. Namely, we defined the relationship between joint probabilities and conditional probabilities this way:

P(A and C) = P(A|C) * P(C).In fact, we could keep going for joint probabilities of more than two events. Suppose we added event B to the joing event {A and C}. Then, following above

P(B and A and C) = P(B|A and C) * P(A and C)

= P(B|A and C) * P(A|C) * P(C)In the second line, we used the previous result. This is sometimes written with commas instead of the word “and.” as,

`P(B, A, C) = P(B|A, C) * P(A|C) * P(C).

This unpacking of a joint probability in terms of conditional probabilities is always true, because it follows from definitions. It is only useful, however, if we know the probabilities on the right hand side. In the case of the example we started from, we do. We wanted to know P(Cure AND Approved AND Beaten). It is just

P(Cure AND Approved AND Beaten) = P(Beaten | Approved, Cure) * P(Approved | Cure) * P(Cure)

= (0.1) * (0.6) * (0.3)So this is another way to understand why we multiply the probabilities.

Where do branching probabilities come from?

In our workhorse drug-to-market investment example, we used probabilities prospectively, that is forward-looking, to evaluate expected value. We put some probabilities in by hand. Presumably if we wanted to base these numbers on more than just our imagination, we would look for data from the past (retrospectively). We’re not going to find a lot of data about cancer-curing drugs, but there have been lots of other drugs tested, approved, and/or first-to-market to treat other diseases. Specifically, we would try to find a data set that contained the following column names: Drug, Cost to develop, Success in testing, FDA Approval, First to Market, Total Sales. Or something like that. If we had such a data set, then we could actually fit a tree to it.

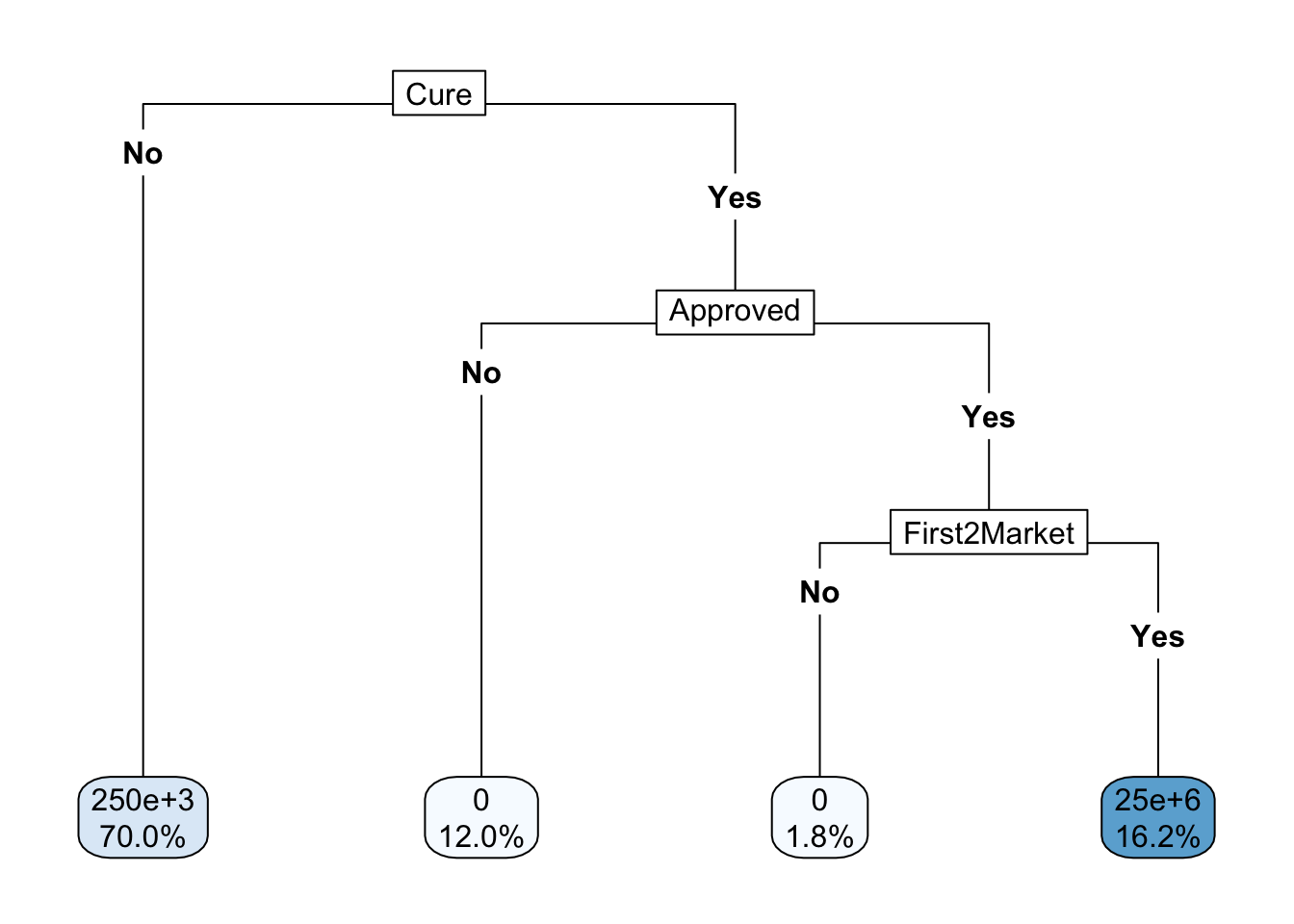

I’ll show you how it is done in principle by making a data set that instantiates Wheelan’s fictional data and then fitting it. I will make 1000 cases using Wheelan’s numbers exactly, which is artificial, but it demonstrates the point. That is, my 1000 cases will have the proportions of outcomes that are dictated by the probabilities we used above. Here’s one way to make the data (you can copy this code and experiment with it in your own R session).

wheelan_cancer <- data.frame(

Drug = paste0("Drug", 1:1000), # this is just a dummy ID

Cure = c(rep("No",700), rep("Yes",300)), # 70% of drugs will fail to cure

Approved = c(rep(NA,700), rep("No",120), rep("Yes",180)),

First2Market = c(rep(NA,820), rep("No", 18), rep("Yes",162)),

Payout = c(rep(250000,700), rep(0,120), rep(0, 18), rep(25000000,162))

)Notice that I had to use the missing value “NA” in the table that I made. If the drug does not cure the disease, the the approval status is neither Yes nor No. It never gets to that stage. So the approval value for those drugs is missing. The data has 1000 rows, many of which are identical. I will show the rows where things change. In between we have a lot of replicas, i.e., drugs with the same exact story.

| Drug | Cure | Approved | First2Market | Payout |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug1 | No | NA | NA | 250000 |

| Drug700 | No | NA | NA | 250000 |

| Drug701 | Yes | No | NA | 0 |

| Drug820 | Yes | No | NA | 0 |

| Drug821 | Yes | Yes | No | 0 |

| Drug838 | Yes | Yes | No | 0 |

| Drug839 | Yes | Yes | Yes | 25000000 |

| Drug1000 | Yes | Yes | Yes | 25000000 |

Now this last part is a bit of black magic, since I have not said anything about how one “fits” a tree, also known as a recursive partition, to data. But here it is. It can be done using a R package called rpart (for recursive partitioning).

library(rpart)

library(rpart.plot)

wheelan_tree <- rpart(

Payout ~ Cure + Approved + First2Market,

data = wheelan_cancer,

method = "anova"

)Ta-da! Don’t believe me? Here is the tree.

rpart.plot(wheelan_tree, type = 5, digits=3)

The leaf nodes at the bottom (rpart makes top-down trees) show the payout using scientific notation. I don’t know how to suppress that. You can see both the payout and the probability of the payout.

Hopefully you can see that expected value is quite general. You could use this kind of thinking, for example, to estimate your future income based on decisions you can make about your life. Suppose you major in acting AND you get discovered on the streets of Greenwich Village AND your indie debut film leads to superstardom as the next Marvel superhero! But what if your indie debut never gets off the ground? What if you had majored in accounting instead? Maybe you went to work for a big investment bank, or perhaps it was just a small tax office. If you assign numbers to the scenario above, you can calculate the expected value of your college major in terms of earnings.

Of course, there are no guarantees, only probabilities.