Chapter 3 Tests of independence: A first look starring alternate universes

So far, we have looked at some data in two-way tables and judged them by inspection. That is, we looked at them and said, these two responses appear to be deterministically related, or they appear to be associated but not deterministically, or they appear to be independent. But we acknowledged that our data come from a sample, and that on another day (on in another universe with rules the same as this one), we might have observed slightly different data.

It is worth noting that a single dataset often can’t tell us for sure whether two variables are independent or associated (aka dependent/contingent), and whether or not an association is a deterministic one. (Two variables cannot be deterministically independent; that would be a self-contradiction.)

In this chapter, we’ll take a first look at how a particular two-way table might have come about, and thus how it might have come out differently. Let’s suppose that we observe the data summarized here:

| chunky | smooth | |

|---|---|---|

| over | 17 | 6 |

| under | 5 | 12 |

It looks like certain pairs of outcomes are coming up more than we would expect “by chance” if the answers were not associated. Equivalently, it looks like there is an association between these variables, but let’s investigate further. Let’s take the cell with the largest number of people in it, or the modal value. In this case, the mode occurs for people who answer over and chunky. Which was 17 out of 40.

Now consider what contributes to making this particular value what it is. For example, what would make it bigger? Well, if there were more over-hangers than under-hangers, that would tend to increase the number of people who could be both over-hangers and chunky-spreaders. Similarly, if there were more chunky-spreaders. Also, if there were just more people in our sample, then of course we could have more people in this cell of the table. And all of the above arguments could work in reverse, if we lowered any of those particular numbers.

What if, for argument’s sake, we fixed the total number of people, the number over-hangers among them, and the number of chunky-spreaders among them. We’re going to keep these values constant while letting the individual table elements vary. The technical term for this, by the way, is fixing the marginal values. This is because the sums of the columns (22 and 18) and the sums of the rows (23 and 17), when written at the bottom and side of the table, are called margins (just like the margins of a page). We could still have fixed the marginal values and have different values in the table. For example,

|

|

Notice that the row and column sums are the same. But on the left we would say an association between the variables appears even more clear, whereas on the right, it appears less obvious. Can you see why?

Recall that the actual data summarized in a two-way table originally came from some observation sample. There were 40 people sampled, and they were each asked two questions. Before we tabulated them, the data might have looked something like this:

| Peanutbutter | Toiletpaper |

|---|---|

| Smooth | Under |

| Chunky | Over |

| Chunky | Under |

| Chunky | Over |

| Smooth | Under |

Now suppose we wrote every person’s response to the peanut butter question on an index card, shuffled them randomly, and then re-distributed them. We then did the same for the toilet paper question. We did this one question at a time, separately. Finally, we ask our sample to show us their cards, and we treat these paired observations as a new data set. We generate a new two-way table from the results. If we do all this, then we will have kept the total number of people the same, as well as the total number of “over” answers and “chunky” answers. Moreover, since we shuffled responses to each question separately, there is absolutely no way for someone’s randomly assigned answer to one question (the index card they got for peanut butter) to influence their randomly assigned answer to the other (the index card for toilet paper). The answers should, by definition, be independent.

Rise of the machines

Well, we can do this shuffling experiment very easily on a computer. And we can very easily repeat it 1000 times. So, the question we might then ask is, how many times out of 1000 such simulations do we get a value for over and chunky that is as large as (or bigger even) than 17?

The code to do this, and to visualize the outcome, is below. (You do not need to understand this code yet, but some of it might make sense to you).

simulated_overchunky = c() #initialize empty vector

for(i in 1:1000){

# the sample() function does the shuffling

shuffle_data$Peanutbutter = sample(shuffle_data$Peanutbutter)

shuffle_data$Toiletpaper = sample(shuffle_data$Toiletpaper)

# the table() function does the tabulating

simulated_overchunky[i] = table(shuffle_data)["Chunky","Over"]

}

# plot the results using a histogram

hist(simulated_overchunky,

main = "",

xlab = "Count",

breaks = seq(0,20,1))

abline(v=17, lwd=2, col=3, lty=2)

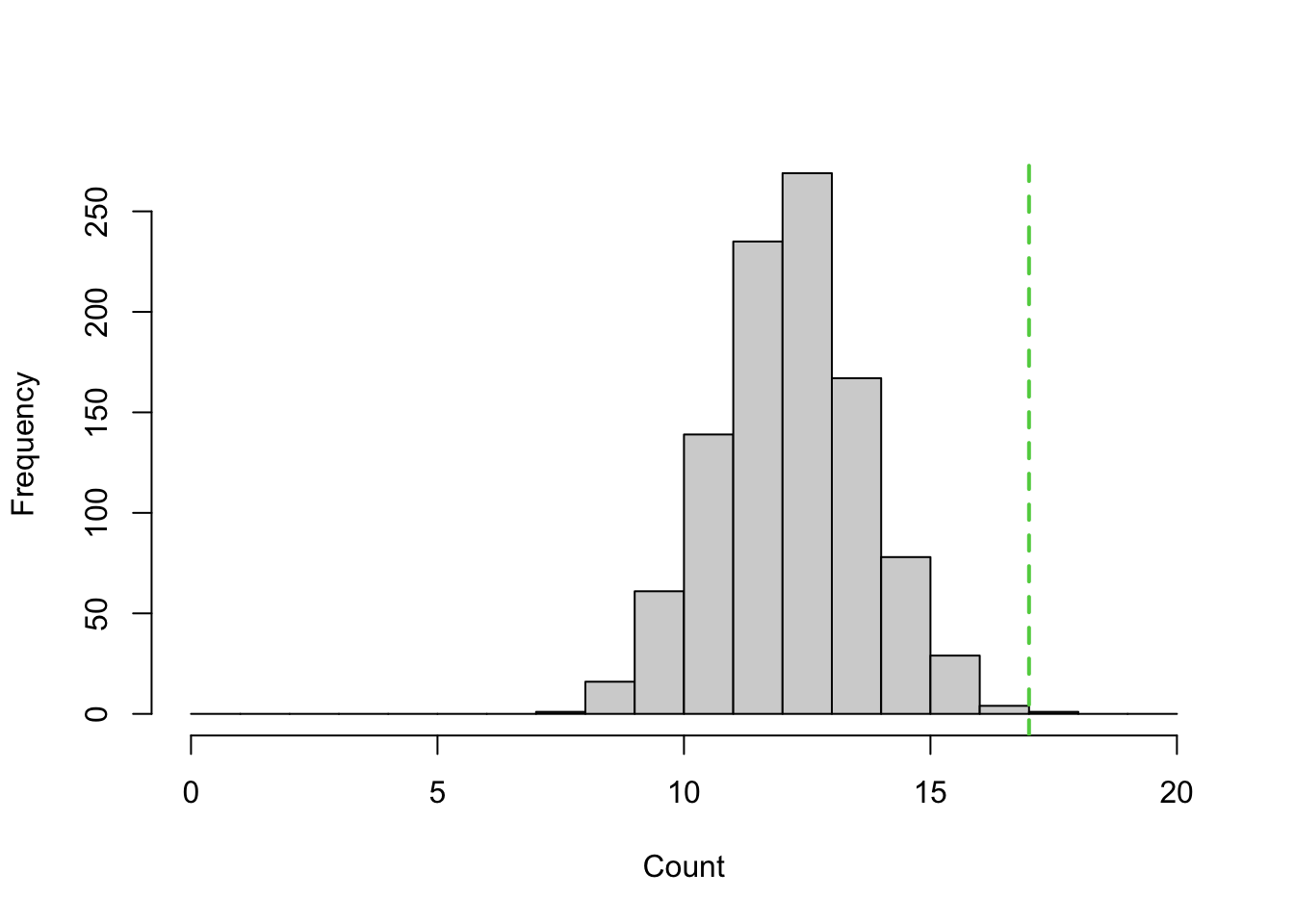

Figure 3.1: Counts of ``over and chunky’’ after 1000 shuffling simulations

Figure 3.1 is histogram, or a bar plot of count data. We will cover histograms in detail the next chapter, so don’t worry too much if some of this is still confusing. The main thing to notice is that green dotted line at 17, and this: in our 1000 shuffling experiments, we got values greater than or equal to 17 only 5 times. (You probably can’t see this in the histogram, but if you run the code, you can ask R to report this: length(which(simulated_overchunky >= 17))) The rest of the time, the values were smaller, and typical values were around 13.

This simulation we just carried out is a way of validating our intuition, from inspection of Table 3.1, that 17 was a high value if toilet paper orientation and peanut butter preference were indeed independent. What we showed is that, if indeed the two variables were independent, that such values would be observed only rarely. Since this value was observed on our first day out in the park (in this scenario), we begin to doubt independence. If on the other hand, we had observed 13 over-chunky people (out of 40, and with the same marginal values as before), then we would say that this observation seems quite consistent with independence. Because values near 13 occur very often in our shuffling simulation.

Hypothesis testing just happened

What we just did is in fact an example of a hypothesis test. In the statistical framework of hypothesis testing, we have a null hypothesis (usually, a skeptical position) and an alternative hypothesis. Here our null hypothesis was that the two variables represented in our response data are independent. Our alternative hypothesis was that people who are over-hangers are truly more likely to be chunky-spreaders. We didn’t state this hypothesis at the outset. But it was implied by the fact that we were investigating this “high” value in the contingency table. If you take a regular statistics class, however, you will see that, when it comes to inference, it is quite important to take care in constructing your null and alternative hypotheses. For now, we just want to get the main idea.

The main idea was that we simulated what data might look like under the null hypothesis (independence) and checked if our observations were consistent with that or not. Consistent (with the null) results would mean that we cannot “reject” the null hypothesis, while highly inconsisent results give us justification to “reject the null” in favor of the alternative. In this example, we would probably reject the independence assumption (null) in favor of the alternative. The independence assumption was consistent with values around 13 plus or minus 3 (i.e., the range of 10-16). But 17 is unusually high.

Caveats

Rare events still do happen, rarely. What our simulation showed us is that high values do still happen by chance. Even if the variables were independent, if we sent 1000 people out in the world to collect data from samples of 40 people each, some of those people would observe large values that look associated. This is to be expected. This is why it is important, if we are seeking the truth, that we not game the system by checking over and over again until we get an answer that we like. This would be like rolling double-sixes on the fourteenth try and then saying “ha! see, I told you I was lucky.”

What about the other cells in the table? You might be wondering how we can do this whole simulation just for the one cell in the table that corresponded to over-chunky. You’re right to wonder this (if you are). In time, we will see that we can do independence-tests (or other hypothesis tests) more democratically by examining all of the cells in the table and how they differ from what we would expect under the independence (null) hypothesis. For now, though, note the following. Each of our variables is dichotomous, and we fixed the row and column marginals (totals). So if over-chunky is high, and total count of chunky is held fixed, that means that under-chunky must be low. Our test would have gone the same way if we sought to explain that cell. So, too, must over-smooth be low (lower than it would be under independence assumptions).

Sampling, simulations, and randomness

In the last section, we used the sample() function in R to shuffle some values in our simulation. That is, starting with a data set of 40 responses (for example, 23 “over” responses and 17 “under” responses), we wanted to reassign these responses randomly among the people in our observation sample. What if we wanted to simulate the original set of answers in the first place? It turns out we can also use the computer without collecting any data at all.

To reproduce the exact example above, it would suffice to write down a series of values like this (over, over, over, over, …, over, under, under, … , under), 23 overs and 17 unders, and then shuffle them. Boom. The first shuffle is our simulated data. But that procedure wouldn’t work if we wanted a sample of 3, would it? If we want to be able to simulate data with different sample sizes, we need another approach.

Tossing (virtual) coins

Let’s simplify things for a minute and assume that in actuality, people are equally likely to be over-hangers or under-hangers. Or that for whatever dichotomous question we want to ask, the likelihood of either responses is 50%. If you want to simulate an event that has a 50% chance (or probability of 0.5), you can toss a coin. If we want to randomly assign 10 people to one of two groups, say the Sharks and the Jets, we can do the following. First, decide that Heads we choose Sharks (this is, of course, arbitrary). Then, for each person, flip a coin. If heads, then assign them to Sharks. If tails, assign them to Jets.

Another way to do this is to put two poker chips into a hat, say a red chip (for Sharks) and a blue chip (for Jets). Then blindly reach into the hat and pick out one chip, record the value, and then put it back and shake the hat before the next draw.

Pulling a chip out of a hat or tossing a coin are equivalent manifestations of the ideal process of sampling a random event with a 50% chance. This is actually a profound idea. The coin toss or hat draw are concrete, mechanical processes. Each has two possible outcomes (heads/tails or red/blue), and, for all intents and purposes, the outcomes in both cases are equally likely. We human beings have learned to abstract from both of these mechanical processes to an idea of a stochastic process which is the same thing as a random process and the exact opposite of a deterministic process. This abstract process requires that we have a state space, which is just a set of possible outcomes (mathematicians refer to some sets as spaces). As long as the set has two possibilities, it doesn’t really matter whether we label them heads/tails, over/under, red/blue, Sharks/Jets, or 0/1, because the label can always be assigned to mean whatever we want it to mean (just as we decided heads corresponds to Sharks). In addition to the state space, we abstract the idea of the sampling process. This is what “picks” out one of the possible outcomes. Like the coin-flip or the hat-draw. And it is this sampling process where the probability of the outcome appears.

We can in fact simulate this sampling process on the computer in R. In fact we can do it several different ways. Here, first, is a more or less direct translation of what our mechanical process would do. The key enabling function here is called sample(), which works just like pulling chips out of a hat. We will tell sample() what’s in the hat by defining a set (a vector, in R) called coinstates. Then we will sample once from the hat for each person.

set.seed(8675309) # I'll explain this later

coinstates <- c("H","T")

numPeople <- 10

# start a blank list to hold my team assignments

teamassignments <- c()

# now, go one by one; this is called a programming "loop"

for (i in 1:numPeople) {

## toss coin and observe

coinresult <- sample(coinstates, 1) # the 1 means sample once

# associate outcome with team assignemnt

if (coinresult == "H") {

team <- "Sharks"

} else if (coinresult == "T") {

team <- "Jets"

}

# record team assignment

teamassignments <- c(teamassignments, team)

}

teamassignments## [1] "Jets" "Sharks" "Jets" "Sharks" "Jets" "Sharks" "Sharks" "Sharks"

## [9] "Jets" "Sharks"Voila. The sample function did the apparent work of the coin flip or, equivalently, picking a “Heads” or “Tails” out of a hat containing both. Just as good, right? Notice that (a) we only got four Jets, not five, and (b) sometimes we got three Sharks in a row. That’s randomness for you.

Technically, it is pseudo-randomness. Notice the first line of the code where I set the “seed” for the random number generator. What this does is make sure that every time I run this code I get the same results. If that seems not random to you, I don’t blame you. But here are some important things to keep in mind. First, even though using this random seed makes my experiment repeatable, I still have no idea what the results are going to be until I run it the first time. Second, if I change the seed, even by a tiny amount, then I will once again have no idea. Try it yourself. Note that if you do not declare a random seed, then the computer will effectively choose one for you, perhaps by using the exact computer time in milliseconds. This way the results will still be different every time you run it. If you want to read (a little bit) more about randomness, see the Appendix.

If you’re thinking we could have removed the coin from this process, you’re right. Coins are not essential to this process. We could imagine a mechanical device that drops marbles into jars directly, provided that we believed the marble dropping process was equivalent to the coin flip in terms of 50/50 chances. In R, here is a faster way. We just sample out of a “hat” containing each of the team names.

set.seed(8675309) # same seed, on purpose

teamnames <- c("Sharks","Jets")

numPeople <- 10

teamassignments <- sample(teamnames, numPeople, replace=TRUE)

teamassignments## [1] "Jets" "Sharks" "Jets" "Sharks" "Jets" "Sharks" "Sharks" "Sharks"

## [9] "Jets" "Sharks"Well, that was simpler. Notice also that by using the same random seed, I got the same team assignments, even though the code was completely different. (By the way, the [1] and [9] here are just index–count–values that R writes out when the data flow across multiple rows. So you know that the first value on the second row is in fact the 9th element of the vector.)

There’s another difference here, which is that instead of going one by one for each person, I made the selection all at once by passing the number of people to the sample function instead of asking for one sample. Because I’m sampling numPeople times and there are only two outcomes (“in the hat”), I have to add the argument replace = TRUE when I call the sample() function. This means that after I look at the result, I put it back in the hat (I replace it), and then draw again. Otherwise, I could sample only as many times as I have choices.

Sampling without replacement is suitable if, as in the independence test from earlier, all I wanted was to put a set of choices in random order. As we said, this is like shuffling a deck of cards by dropping the deck into a big bag, shaking it, and then pulling the cards out one by one. No replacement.

But some observations do occur more than others

To complete the functionality of our data-generating machine, we need a way to extend this sampling process to outcomes that are not equally likely. What if we want to base a simulation on the observed proportion that 23 out of 40 people chose “over” and only 17 chose “under”, but we only want to sample 10 people?

Once more, I will show you two ways to do this. The first way is to put all 40 virtual cards into our virtual hat, and sample 10 times (with or without replacement? what do you think?). The second way involves abandoning our connection to these virtual cards and replacing them with the mathematical abstraction of a probability.

First, the virtual cards:

set.seed(2125551212) # I can choose any see I want

tp_cards <- c(rep("over", 23), rep("under", 17))

numPeople <- 10

simulated_tp <- sample(tp_cards, numPeople, replace=TRUE)

simulated_tp## [1] "over" "over" "under" "under" "under" "under" "under" "over" "under"

## [10] "over"Hopefully this code seems pretty straightforward. Why did I use replace=TRUE? I didn’t need to do that, since I was only drawing 10 samples from a hat with 40 cards. However, by replacing the card I drew each time, I made sure that the chances were the same for each virtual person in my sample.

Suppose that I did not replace the samples each time. And suppose that, by dumb luck, I drew five “unders” in a row on my first five draws (this sequence did actually happen on draws 3-7 above). The sixth draw is now coming from a hat with 23 overs and 12 unders. That draw definitely has different chances of coming up under, and, importantly, it is not independent of what happened before. In real-world sampling, I do not expect the answer from the sixth person I ask to depend on the answers given by the previous five. So it is essential that my simulation have this same property. (Of course, it is true that the proportions in the hat changed even after the very first draw, assuming I don’t replace the cards, but I used the sixth draw to make it more obvious.)

Think about this: Now that we have added replacement to the sampling process, if we change the sample size to 40 (

numPeople <- 40), are we guaranteed to get 23 overs and 17 unders?

Now for the second way. I don’t really need to produce 40 cards at all. I just need to recognize that 23/40 or 0.575 is my target probability of “over” on every single sample. (17/40 or 0.425 is the probability of “under” automatically). I can still do everything with the good old sample() function.

set.seed(2129981212) # I can choose any seed; I like using phone numbers.

numPeople <- 10

simulated_tp <- sample(c("over","under"), numPeople, replace=TRUE, prob=c(0.575, 0.425))

simulated_tp## [1] "under" "over" "over" "over" "under" "under" "under" "under" "under"

## [10] "over"set.seed(2129981212) # if I want to same results

simulated_tp <- sample(c("over","under"), numPeople, replace=TRUE, prob=c(23/40, 17/40))

simulated_tp## [1] "under" "over" "over" "over" "under" "under" "under" "under" "under"

## [10] "over"There it is. For good measure, I included the probability expression using decimals and fractions, to prove that it doesn’t matter to R. I did, however, reset the random seed, otherwise I would not have gotten the same results.

Recap

In this chapter, we used computer simulation to overcome one of the limitations of a single data collection with a small sample. We introduced the R function sample() which can be used to either shuffle a bunch of data in random order or to select (i.e. sample) some data from a larger set. We saw a couple of different ways of doing this, some in which we literally create the large set and some in which we use probabilities instead that “act like” we have a larger set. More importantly to the original goal, using the R function sample() we saw that we can create many replications of simulated data collections. We can use these replications to see what answer-pair observations are consistent with independent answering processes and what observations seem highly unlikely if the answers are truly independent.

Notice that we keep using this language of likely/unlikely, consistent/inconsistent, etc. None of our results “prove” independence or association between question pairs. That’s just not possible with stochastic/random processes and finite samples. We need to be able accept this condition of uncertainty. Note, though, that if we get larger and larger samples, there are some statements that we can make with more and more confidence. Statistics does not eliminate uncertainty, but it can be used to put precise bounds on it.