Chapter 10 Some facts about Probabilities

In this course, I have taken the strong position that ideas should be driven by questions. So I’ve tried to reason through the example above before setting up any foundations on the basic rules of probability. A standard introduction to these topics can be found in many books, for example OpenIntro Stats, Chapter 3.

Now is probably a good time to recap some of what we have established about probabilities. We will also introduce the most basic notation P(A) for the probability that event A happens. For example, event A can stand for “you die at age 64” or “it rains in New York tomorrow.”

- When possibilities are disjoint, or mutually exclusive, the probability that either one of them happens is the sum of the individual probabilities

P(A or B) = P(A) + P(B)

An example of this was dying at age 62 or dying at age 64.

- A special case of this addition rule applies when one or the other MUST happen. For example, in logic, either something happens or it doesn’t happen. Either A or NOT A. Since these possibilities are disjoint:

P(A) + P(not A) = 1

P(not A) = 1 - P(A)

An example of this was the probability that you do not die at age 0. We found it by subtracting out the probability that you will die from 1.

The last fact we used is

- The joint probability rule for independent events that BOTH occur is the product of the individual probabilities of each event occurring.

P(A and B) = P(A) * P(B)

We used that to figure out how you survive by not dying every year. Notice that I’ve snuck in the word independent (well, I snuck it in boldy, so it wasn’t that sneaky). There is an intuitive reason why it is important to make a distinction about independent events.

In the last module, we said that two events (we were talking about responses to questions) are independent if knowing about one of them does not give you any information about what the other one might be. But remember bizarro world where the toilet paper orientation and peanut butter preference were deterministically related, and specifically everyone is either under-chunky or over-smooth? I’ve reproduced this result in Table 10.1. If I told you that 53% of the total population prefers smooth, then what proportion of the total population prefers smooth AND likes to over-hang? Also 53%. What proportion prefers smooth AND under-hangs? 0!

| chunky | smooth | |

|---|---|---|

| over | 0 | 23 |

| under | 17 | 0 |

In bizarro world, toilet paper orientation and peanut butter preference are NOT independent, because knowing one of them DOES give you information about the other.

P(tp = over AND pb = smooth) does NOT equal to P(tp = over) * P(pb = smooth)This will become even more clear in the next section.

Conditional Probabilities

Recall that we would NOT have gotten the right answer to the probability of dying in your 60s if we added up the mortality rates qx for all ages x in [60-69]. (Exercise: verify this.) Rather, we had to multiply these numbers first by the probability of living to age x. Another way to say this is that the mortality rate qx was actually a conditional probability. It was the probability of dying at age x on condition that you have survived to age x. To be absolutely clear, we are measuring x in whole numbers, like birthdays, but we don’t mean dying on your xth birthday. Rather, we mean dying anytime between turning age x and turning x+1. We need a special notation to distinguish conditional probabilities. We write,

qx = P(You die at age x | You survived to age x)and we read this as “qx is the probability that you die at age x given that you survived to age x” or as “qx is the probability that you die at age x conditional on your surviving to age x.” These are equivalent, but they differ from

P(You die at age x)which is the unconditional probability that you die at age x. This is also different from

P(You die at age x AND You survived to age x)which is called the joint probablity of the two events. (Note that the joint probability of events A and B is also often written as P(A, B). The comma functions like the word “and”.) We calculated exactly this joint probability above when we wanted to add up the probabilities that you die at some point in your 60s. The way we computed the joint probability for each year was by application of this general rule for conditional probabilities

P(A and B) = P(A|B) P(B)which we read as “the probability of both A and B happening is equal to the probability of A conditional on B multiplied by the probability of B.” Note that this rule always holds. That’s because what I’ve called the general rule is equivalently just the definition of conditional probability. For example, I could have written it this way:

P(A|B) = P(A and B) / P(B)This is just a rearrangement of the formula, but we have a tendency of seeing whatever is on the left side of an equation as being defined by what is on the right.

As far as death is concerned, the following are all true:

P(die at x AND survived to x) = P(die at x | survived to x) * P(survived to x)

P(die at x AND survived to x) = qx * P(survived to x)

qx = P(die at x AND survived to x) / P(survived to x)where in the second line I substituted the mortality rate qx for the conditional probability that defines it. In the last line, you can see how the mortality rate could be estimated from data if you actually observed a whole bunch of people. You would count how many of the die at age, say, 62, and divide that number by the number who survived to age 62. You can also probably see why the following is true:

P(survived to x | die at x) = 1That is, if you died at 62 then you must have survived to that age. That may seem too obvious for words, but it helps to show clearly that for conditional probabilities, it is not generally true that P(A|B) = P(B|A).

Considering toilet paper in bizarro world, we can see explicitly why the rule for joint probabilities of independent events P(A and B) = P(A) * P(B) did not hold. The conditional probability relationship always holds, but independence is a special case. We can see what it is now:

P(A and B) = P(A|B) P(B) = {only in special cases} = P(A) * P(B)Thus, when A and B are independent, it must be true that

P(A|B) = P(A) # for independent eventswhich reads as “the probability of A conditional on B is equal to the probability of A (regardless of B).” Another way to say this is that no matter what we know about B, it doesn’t tell us anything informative about A.

In the real world, this is true about toilet paper and peanut butter.

P(tp = over | pb = smooth) = P(tp = over) ## real worldBut that was NOT true in bizarro world, where knowing peanut butter preference told us EVERYTHING about toilet paper orientation. If A is the probability that a person is an over-hanger, and B is the probability that they prefer smooth peanut butter, then

P(tp = over | pb = smooth) = 1 ## bizarro world

P(tp = over | pb = chunky) = 0However, regardless of whether we stay in the real world or in bizarro world, the following will always be true,

P(tp = over AND pb = smooth) = P(tp = over | pb = smooth) * P(pb = smooth),because this is the definition of conditional probability. Now you might notice that if the above is true, then the following should also be true:

P(pb = smooth AND tp = over) = P(pb = smooth | tp = over) * P(tp = over).And it is true. For the same reason that this follows from the definition of conditional probability.

The order of the two joint events on the left-hand-side does not matter. There is no difference between P(A and B) and P(B and A). If both A and B happen, they both happen. There is no implied chronology when we write “A and B” that A came before B. So, that said, it is also true that

P(tp = over | pb = smooth) * P(pb = smooth) = P(pb = smooth | tp = over) * P(tp = over).By combining the two equations from above. Or, in general

P(A | B) * P(B) = P(B | A) * P(A)Notice that is not generally true about conditional probabilities that P(A|B) = P(B|A). Even though it is always true about joint probabilities that P(A,B) = P(B,A) (I used commas instead of “and” here.) Here’s an example. All NYU students are New Yorkers (at least, honorary New Yorkers while in town.) But not all New Yorkers are NYU students. The probability of being a New Yorker conditional on (or given that) you are currently an NYU student is 1. However the probability of being an NYU student conditional on being a New Yorker is clearly not 1.

Conditional death, again

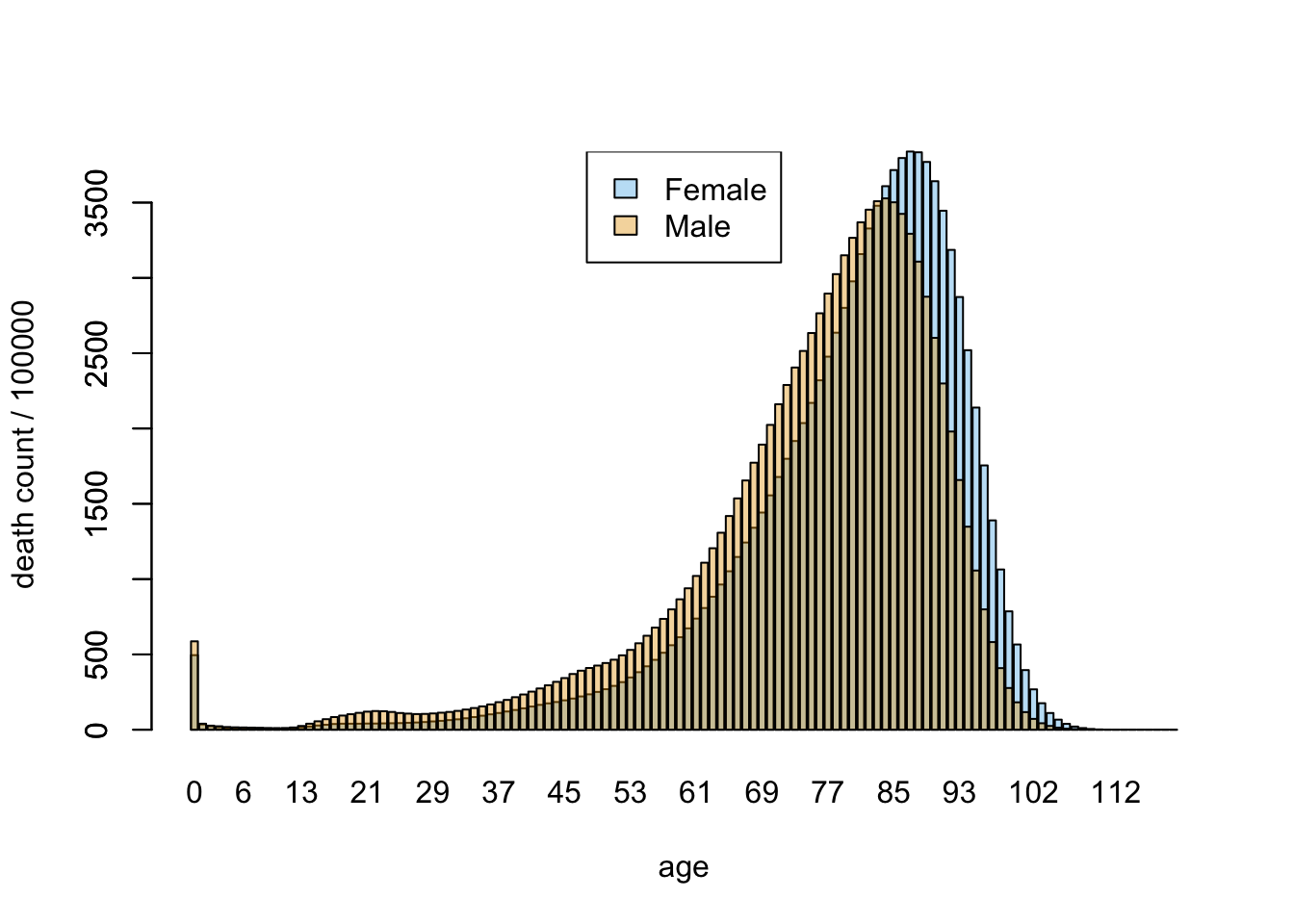

Earlier I said we would use the life table to answer questions about when you will die assuming nothing else about you. Now, you might be aware that life expectancy is not the same for males and females. Indeed, there are separate life tables for each sex. I’ve plotted the death column dx from both tables in Figure 10.1. Females are shown in light blue bars, and males using orange. Unfortunately for the males, their mortality rate is higher not only in their later years, but even in their late teens and twenties. (We’ll come back to that when we consider how you will die.)

Figure 10.1: Deaths by age for male and female (2010)

Suppose I was interested purely in the likelihood (at birth) of living into ones 90s or beyond, conditional on sex. I can find out the proportions from separate life tables for each sex as follows. (These single-sex life tables go from 0 to 119, and the first row is dying before your 1st birthday. I need to look at the 91st row to see death after age 90.):

#proportion of females dying from at ages 80-119

sum(lifetableFemale[91:120,"dx"])/sum(lifetableFemale[,"dx"])## [1] 0.2446278#proportion of males dying from at ages 80-119

sum(lifetableMale[91:120,"dx"])/sum(lifetableMale[,"dx"])## [1] 0.1347719I can make a two way table using these proportions. I will base my table on a sample of 1000 females and 1000 males. This is not real sample data. I am just using the life table proportions here to construct an idealized sample.

sex_age80 <- data.frame(dieBefore90 = c(755,865), livePast90 = c(245,135),

row.names=c("Females","Males"))The table looks like this

| dieBefore90 | livePast90 | |

|---|---|---|

| Females | 755 | 245 |

| Males | 865 | 135 |

The unconditional probability of living past 90 is (245+135)/2000 = 0.19 or 19%. This would be your betting chances if a baby were born and you did not know its sex. We can write this as P(live past 90) = 0.19. But if you knew it was born female, then you need to compute P(live past 90 | sex = female). How would you do this? Well, you can use the table. Of the 1000 females, 245 live past 90, so the answer is 24.5%. For males, it is 13.5%. Sorry, males.

Just to make things weird

Now suppose, for arguments’ sake, that the numbers in the life table apply to everyone born in the last 120 years as of today (they don’t; life expectancy has changed over the years). If I told you that someone was over 90, but nothing else about them, what is the probability that the person was female at birth (we will make the simplifying assumption that the life table corresponds to sex at birth)? The two-way table I constructed had equal numbers of males and females. We will assume that the birth rates are indeed the same. So the unconditional probability of being born female knowing nothing about a person’s status as living or dead is 50%. However, among those alive in their 90s, 245/(245+135) = 0.64 of them are female. Almost 2 to 1.

Given a two-way table, with variables representing events A and B, it is possible to derive conditional probabilities in both directions. P(A|B) might be the probability of living past 90 given sex at birth. P(B|A) would then be probability of sex at birth given present age over 90.

In the next chapters, we will start to examine what kinds of things might kill you. This will give us another chance to look at association in two way tables (as distinguished from independence). We will also explore what it means to say that something causes early death. In the example above, we saw that sex is associated with early death. Females live longer; males die younger. Would we say that sex causes early death?